Brutalism in Detroit

February 12, 2016

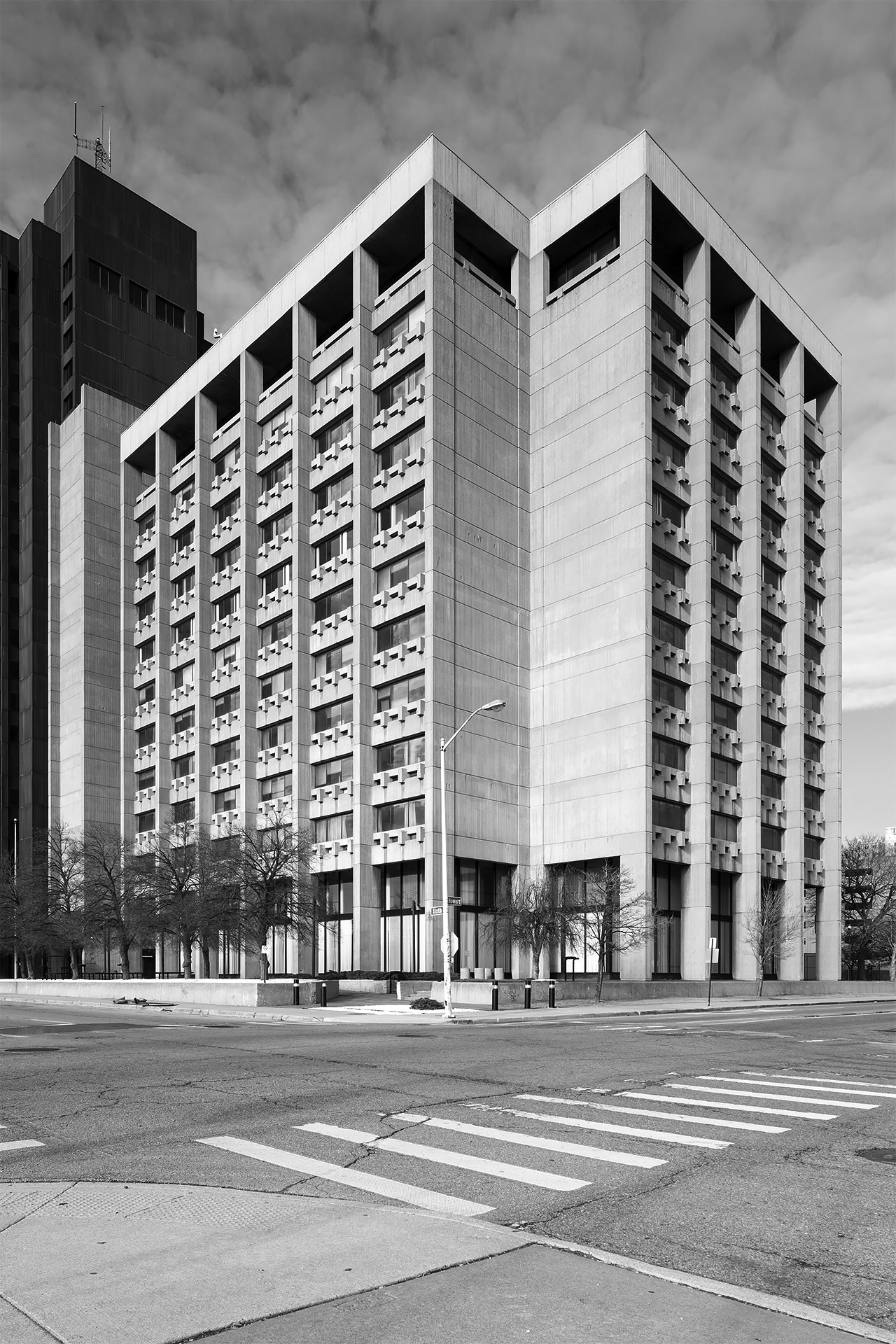

Frank Murphy Hall of Justice in Detroit, Michigan by Eberle M. Smith. Photo by Jason R. Woods.

One of the reasons I love Detroit is because of its rich architectural history and wide variety of styles. An enthusiast of any era can find gems in any given corner of the city; Gothic, Renaissance Revival, Art Deco, Modern, Postmodern, and everything in between. One style that generates perhaps the most polarizing emotions is Brutalism, deriving from the French term béton brut, meaning “raw concrete.” You know it when you see it, and you likely either love it or hate it.

Over the past six months, I’ve come to love Brutalism for its aesthetic qualities, clear and concise language, and its bold, unapologetic nature. The use of raw concrete on a massive scale creates some unique opportunities as well as challenges. On the positive side, it is exceptionally durable and resilient; it is no wonder that the core of the tallest building in the world (Burj Khalifa) is made of concrete, bomb shelters are frequently made of concrete, the list goes on. Concrete is also versatile in terms of design, since it will take the shape of virtually any form you pour it into. Some will argue it is more cost effective in the long term, as it requires relatively little maintenance compared to other building materials.

Unfortunately not everyone shares my enthusiasm for Brutalist architecture. It seems that nearly every significant example has seen strong opposition and threats of demolition. Many of the greatest Brutalist structures have been completely, or at least partially demolished. A huge portion of the aforementioned Armstrong Rubber building was razed in 2000 and was replaced by a parking lot for Ikea.

The vast majority of Brutalist structures can be found throughout Europe, most of which were conceived following the second World War. But those looking for examples in America usually don’t have to travel too far. The east coast bears notable examples like Boston City Hall, Breuer’s Whitney Museum of American Art in New York as well as the Armstrong Rubber Headquarters in New Haven, CT. The west coast is known for the radical Geisel Library and even more famously, Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute.

The Midwest lays claim to a few impressive examples as well. Marcel Breuer left us St. Francis de Sales in Muskegon and St. John’s Abbey Church in Minnesota, Chicago holds a some impressive works as well. A handful of Brutalist buildings can be found in Detroit, all with varying approaches to the medium.

Frank Murphy Hall of Justice in Detroit, Michigan by Eberle M. Smith. Photo by Jason R. Woods.

Frank Murphy Hall of Justice in Detroit by Eberle M. Smith. Photo by Jason R. Woods.

Shapero Hall of Pharmacy on the campus of Wayne State University in Detroit by Glen Paulsen. Photo by Jason R. Woods.

Detroit Trade Center by Jickling Lyman Powell Associates, Inc. Photo by Jason R. Woods.

Detroit Trade Center by Jickling Lyman Powell Associates, Inc. Photo by Jason R. Woods.

Patrick V. McNamara Federal Building in Detroit by Smith, Hinchman & Grylls. Photo by Jason R. Woods.

Patrick V. McNamara Federal Building in Detroit by Smith, Hinchman & Grylls. Photo by Jason R. Woods.